2018

January

21-31

|

"Rare super blue blood moon eclipse" — what?!

The media are all agog about the "rare super blue blood moon eclipse" about to

happen on Wednesday morning. What's really going on?

Quick answer: We have an eclipse of the moon, only partly visible from the eastern U.S.

The West and Asia will get a better view.

It starts at 6:48 a.m. EST on January 31, which, as seen from Georgia, is just

before the moon sets; we don't get to see the moon completely eclipsed.

No eye protection is needed since this is the moon, not the sun.

For more information click here.

Is there anything unusual about it?

Well... blood moon is what some religious cultists have started calling all eclipses of the moon.

The moon typically looks reddish when eclipsed, due to light reaching it edgewise through the

earth's atmosphere. There is a lot of nonsense

about "blood moons," circulating among a sect of Christians who picked up some

kind of "prophecy" that is not in the Bible.

OK then, super. "Supermoon" means the moon is near its minimum distance from earth.

It reaches minimum some time every month, and sometimes that coincides with full moon;

sometimes it even coincides with an eclipse. Depending on how narrowly you define supermoon,

a few percent of lunar eclipses occur at supermoon; they're not excessively rare, and they

don't have any astrophysical importance.

We had an eclipse during "supermoon" in 2015.

Picture and more explanation here;

still more details here.

Finally, blue. Some decades ago, Sky and Telescope Magazine was asked what

the phrase "blue moon" meant in old almanacs, and the answer they gave might not be correct,

but it stuck: A blue moon is the second Full Moon in a single calendar month.

Since most months are longer than the moon's orbital period, this happens occasionally.

As it happens, this month (January) has two Full Moons, February has none (it's the only month

shorter than the moon's phase cycle), and March again has two.

That's an interesting coincidence, but it's not really something to see.

It's just an artifact of our clumsy calendar.

One more thing. Due to a well-known optical illusion, the moon looks bigger

when it's near the horizon, rising or setting.

It also looks bigger when you're paying more attention to it.

This is the main thing people are noticing when they remark about how big the moon looks.

Near the horizon, it is easier to keep your eyes focused on the moon, so you see more

detail in it, and you have trees and buildings to compare it to.

It impresses people more than the moon high up in a blank sky.

So should you go out and see it?

It's interesting to look at the moon at any time. Don't wait for the media to hype something;

go out and enjoy the sky! But take note of the fact that media coverage has gotten out of hand.

They are now reporting every little set of coincidences as "rare."

Almost all my writing time is being spent on Digital SLR Astrophotography, not on the

Daily Notebook. I'll see you in February!

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

January

10-20

|

Short notes

A government shutdown is like quarrelling parents neglecting to feed their children.

Congress has a job, and they're not doing it. We need a mechanism to prevent shutdowns.

Department-by-department budgeting might help, or maybe we need a constitutional

amendment to automatically renew the previous budget if a new one is not passed —

and maybe trigger an election for all of Congress!

On the occasion of the March for Life, I want to point out that there is no necessary

connection between opposition to abortion and right-wing politics.

It could easily have gone the other way —

one might expect capitalists to assert a woman's total ownership of her body

and socialists to want to protect the unrepresented, non-property-owning fetus.

For more on the abortion controversy click here

and here.

I am devoting almost all my writing time to revising Digital SLR Astrophotography.

That's the only reason not much is appearing in the Daily Notebook.

Things are going smoothly here and I'm getting a lot done.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

January

5-9

|

A point on which probability theory is misleading

I'm reading Jordan Ellenberg's

How Not To Be Wrong,

a book whose theme is,

"mathematics is the continuation of common sense by other means."

Ellenberg explains, entertainingly, to the nonspecialist, some mathematical concepts

most of which I've already been using daily for a long time.

And I want to share an adaptation of one of his examples — a point on which classical

(frequentist) probability theory is misleading.

Suppose you're playing with dice, and you roll one of them four times, and it comes up 2, 4, 3, and 6, in

that order.

Then you roll the other one, and it comes up 2, 2, 2, and 2.

Your gut feeling is that the second die has done something unlikely.

But classical probability theory says that 2, 4, 3, 6 is just as unlikely as 2, 2, 2, 2.

A die can give you any number from 1 to 6 any time it wants.

It has no way of knowing whether it's repeating itself.

And on this point, classical probability theory is misleading.

The reason? Classical probability theory doesn't take prior knowledge into account.

The reason 2, 2, 2, 2 strikes you as fishy is that you know that it's relatively easy to

rig a die to roll the same number over and over, and cheaters actually do this.

It's almost impossible to rig a die to roll 2, 4, 3, 6, and we've never heard of

anybody doing it.

So the reason 2, 2, 2, 2 strikes you as unlikely is that it supports a hypothesis that is

unlikely but worth noticing. Your prior knowledge tells you that 2, 4, 3, 6 does not

suggest anything fishy, but 2, 2, 2, 2 does.

A big problem with classical probability and statistics is that they don't tell you how

to change your knowledge. Classically, every experiment and observation exists in

total isolation. I've written about this before.

Another problem with statistics as practiced today is that too many foot-soldiers of

science have been miseducated into believing that

a p value below .05 confirms a hypothesis.

Science becomes a search for p<.05, which dooms it to being wrong about 1/20 of the time!

Some dogmatists even maintain that you must not care about the value of p except whether

it is above or below .05. You have to "choose" .05 as the cutoff point before even doing

the experiment.

That is balderdash. A p value of .001 really does tell you something that a p value of .05

does not. If you blind yourself to that fact, you're ignoring scientific evidence.

In fact, as Ellenberg emphasizes, the original advocate of p values, R. A. Fisher,

never said that p<.05 confirms a hypothesis!

He said it indicates a hypothesis worth pursuing.

Confirmation comes when repeated experiments regularly and reproducibly

produce low p values.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

January

2-4

|

Meltdown and Spectre, or what's wrong with those Pentiums

UPDATE: Don't panic. Use virus protection, keep your computer up to date,

don't take risks with untrusted software, keep calm, and carry on.

If you use the Chrome browser, turn on strict site isolation

as described here.

This setting will soon be made for you by an update. Microsoft Edge and some other

browsers have already made the change.

Microsoft's hasty Windows patch broke some software, notably ASCOM astronomical

equipment drivers, due to an acknowledged bug

(details here).

There are reports of a Microsoft patch that freezes AMD CPUs.

If you have to roll back and hide a Windows update (as described here —

scroll down for it), don't despair.

As long as you use good security practices, your computer is still safe to use.

Wait for new updates, with the bugs fixed, probably coming very soon.

|

There have been some very confusing news reports today that

something is wrong with almost all Pentium CPUs as well

as lots of others, and to fix it, they're going to have to

be slowed down. The flaws have been given the scary

names Meltdown and Spectre.

I don't have full technical details myself, but I want to explain,

in layman's terms, what I know.

IMPORTANT ADVICE: When you are handling confidential data

(such as communicating with your bank), don't have other

software or browser windows open that you don't actually need.

That's because the new vulnerability allows running programs to

spy on each other. Programs can't spy if they're not running.

Remember that nowadays, most browser windows have software of their

own running in them, software that you didn't buy or install.

Don't be paranoid, but do make a practice of not having untrusted

things open on your computer at the same time that you handle

confidential data.

|

What has happened?

A new way has been found for viruses and spyware to do their mischief.

Specifically, a new way has been found for running programs to spy on

other running programs.

It is quite different from anything viruses or spyware have been able

to do until now, so new protections are needed.

Is it dangerous to use my computer?

No. All that has happened is a new opportunity for viruses and spyware.

Ordinary software is not affected.

In fact, there are no reports of viruses or spyware actually using the

newly discovered vulnerabilities yet.

How can I protect my computer?

If you have third-party antivirus software, update it with today's update.

Then get today's Windows update or MacOS update, and stay tuned for more

updates coming in the near future.

I heard it would slow my computer down 30%. Will it?

So far, today's Windows patch slowed my computer down just 3%, judging by

the measured speed of an image-processing application (PixInsight).

I expect the slowdown to decrease as the later patches become more sophisticated.

Will my computer melt down?

No. The names Meltdown and Spectre are needlessly scary.

OK then. What exactly has been discovered?

It has to do with speculative execution, which is a way modern CPUs do their

work faster. Basically, CPU manufacturers have been speeding things up in a way that

wasn't as safe as everyone thought.

Here's how it works. Computer programs constantly have to make decisions, such as,

"If this amount is a deposit, add it; if it's a withdrawal, subtract it."

Modern CPUs can do more than one thing at a time, so in that example,

if the adder and subtracter

aren't already busy, the CPU will both add and subtract the amount

while finding out whether it's a deposit or withdrawal.

Then both numbers will be ready, and it will take the one that's needed and throw

away the other.

That's faster than waiting for the decision before doing the addition or subtraction.

Large parts of all computer programs work this way, and here's the problem:

Ways have been found for a running program to get information about what was on the

road not taken, even information belonging to a different running program.

And that has to be stopped, because it gives viruses and spyware a new way to spy.

In the short term, operating system kernels are being rewritten so that programs don't

get that close to each other. That's where the slowdown comes from.

Nothing important and confidential can be left within reach of this newly

discovered spying technique.

In the long run, the CPUs themselves are going to be redesigned to eliminate the

indirect ways in which spying turned out to be possible.

Is this Intel's fault?

Intel is actually not the only manufacturer whose CPUs are vulnerable, although

their Pentium family (including Core, etc.) is the worst off.

Speculative execution is an industry-wide technique, and nobody was fully aware

of the hazards until just lately.

Do we blame General Motors for not putting seat belts in cars in 1960?

No; the need for them just wasn't appreciated at the time.

The same may be true of the Pentium.

The goal of computer design is to get computers to function well.

Good computer designers have trusted the users not to do wildly unreasonable things.

Nobody foresees new developments in computer viruses, produced by criminals willing

to work extremely hard to get other people's data.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

January

1

|

It's a book!

We proudly unveil the twelfth edition of our longest-running family project

(actually started and led by our good friend Doug Downing, who was the best man at our wedding).

For more than 30 years, we've been tracking down computer vocabulary and explaining it to people.

More information at www.termbook.com.

Permanent link to this entry

And a new tool for photographers

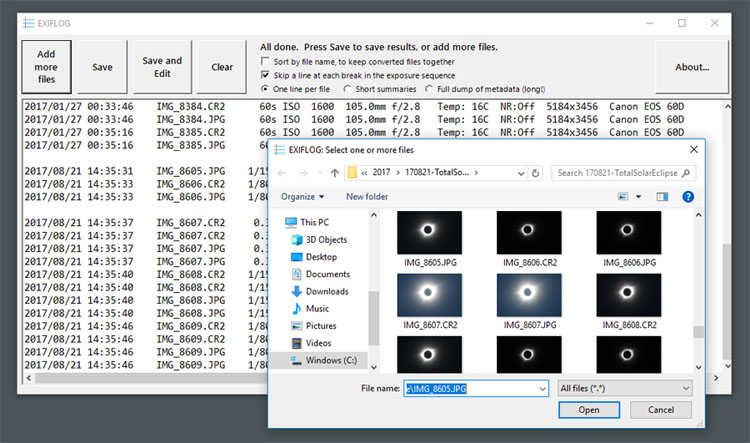

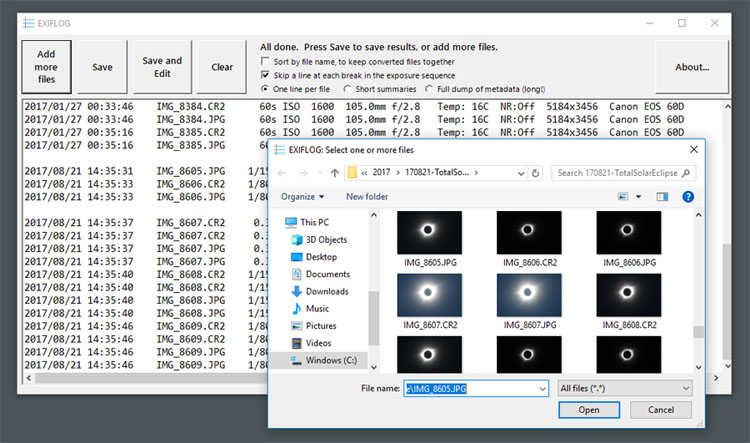

EXIFLOG is a free program that reads digital image files (from your camera) and

gives you a text file listing the exposure data for each one.

I use it all the time for astrophotography logs.

Anybody who wants to make a checklist of pictures will find it useful.

The new edition includes all of Phil Harvey's ExifTool,

which means it can read the metadata from almost any image file, whether or not it

uses EXIF format, and supports every camera Phil Harvey has heard of.

Download and enjoy!

Permanent link to this entry

C#: How to shell out to a command-line app and capture the output, in the background, in a Windows GUI application

I refer you to EXIFLOG, above, which does exactly that.

Download the source code for version 3.1.

Permanent link to this entry

Calendar musings

Happy new year! By now you've heard the hoax that

01/01/2018, 02/02/2018, 03/03/2018, etc., are all Sundays.

That is not possible, of course, and even today isn't a Sunday.

You'd think people would have noticed.

As I've mentioned before,

some people are very gullible about the calendar because they

haven't thought things through.

If I were teaching middle school, I would have sixth-graders make

their own calendars. "Make a calendar for a year that starts on a Monday

and is not a leap year." You can do that (except for the date of Easter)

without looking anything up. It's not rocket science.

We say that a year is 52 weeks, but actually, 52 × 7 = 364

and a year is 365 days long (366 days in a leap year).

That means the weekday for any given date shifts forward 1 day at every year,

and an additional 1 day when a leap year day intervenes.

Today is a Monday; next New Year's Day will be a Tuesday.

(The week runs too fast for the calendar, so to speak.)

Why don't we make a year exactly 52 weeks, by throwing away December 31

and doing away with leap year? Because a 364-day year would not stay in sync

with the seasons. The orbital period of the earth is 365.2422 days.

The shortest day of the year is December 21. If we had a 364-day calendar,

then next year it would be December 22, and the next year December 23,

and so on, gaining 1.2422 days per year, and in a century the dead of winter

would fall in May and the heat of summer in December.

Even if we only did away with leap year, we would face a shift of a day every

four years (nearly), which would get inconvenient after a while.

As it is, our present calendar makes the year 365.2425 days long in the long run,

and that's not quite right. In about 3000 years we're going to need another

adjustment, probably done by skipping a leap year day.

You may notice that some of the type on this page is slightly larger than

it was last month. I am continuing to experiment with fonts. More changes

may be coming, but at present, you are still looking at Google Arimo and Tinos.

Permanent link to this entry

|

|

|

This is a private web page,

not hosted or sponsored by the University of Georgia.

Copyright 2018 Michael A. Covington.

Caching by search engines is permitted.

To go to the latest entry every day, bookmark

http://www.covingtoninnovations.com/michael/blog/Default.asp

and if you get the previous month, tell your browser to refresh.

Portrait at top of page by Krystina Francis.

Entries are most often uploaded around 0000 UT on the date given, which is the previous

evening in the United States. When I'm busy, entries are generally shorter and are

uploaded as much as a whole day in advance.

Minor corrections are often uploaded the following day. If you see a minor error,

please look again a day later to see if it has been corrected.

In compliance with U.S. FTC guidelines,

I am glad to point out that unless explicitly

indicated, I do not receive substantial payments, free merchandise, or other remuneration

for reviewing or mentioning products on this web site.

Any remuneration valued at more than about $10 will always be mentioned here,

and in any case my writing about products and dealers is always truthful.

Reviewed

products are usually things I purchased for my own use, or occasionally items

lent to me briefly by manufacturers and described as such.

I am an Amazon Associate, and almost all of my links to Amazon.com pay me a commission

if you make a purchase. This of course does not determine which items I recommend, since

I can get a commission on anything they sell.

|

|