2020

February

29

|

Is socialism anything in particular?

February 29 is a good day to write about an odd topic, and here is one.

Please not that this is not about the Sanders campaign platform, which

I have not yet looked at closely. This is something I drafted several months

ago.

I am well aware that some of my friends are more expert on aspects of this

question than I am, and that they have widely differing opinions.

But the multiple meanings of the word "socialism" need to be pointed out.

So here we go...

"Socialism" is a hot word as we lead up to the 2020 election.

Lots of people don't quite know what it is but are sure they're

supposed to be against it.

It certainly has a bad name, having been used by the cruel regimes

of both Hitler and Stalin. But what is it? Would we know it

if it weren't called by that name?

It is in fact several things, all of which

(except the first in the list) are in a trade-off

relation against freedom, affordability, and in many cases

incentive to work. That doesn't make all of them totally bad.

It just means we must count the cost. Other systems have

costs, too, which need to be compared.

I've found five,

count 'em, five different things that are called socialism.

I'm approaching this as a linguist, not an economist — not promoting

an economic theory (though I have my opinions!) but rather observing

how a word is used.

One of the five is so vague that I've numbered it (0),

leaving me (1), (2), (3), and (4) to respond to. They are:

(0) The notion that the purpose of the economy is to support

people, not businesses.

This is trivial; only a very short-sighted person would dispute it.

My impression is that this definition is sometimes used

by politicians who are under pressure to

call themselves "socialist" but are not Marxists.

(1) Anti-capitalism; that is, government ownership of businesses,

and in particular, not allowing businesses to be owned by investors.

Capitalism is the system under which businesses can be owned by anyone,

including outside investors. This is good for two reasons.

One is that it makes possible the creation of large companies.

Microprocessors, automobiles, and other complex products can't be made

in mom-and-pop boutiques, at least not efficiently.

The other is that it allows ordinary people to have the experience of

investing in a business, taking the risks, and reaping the rewards.

Socialism, under this definition, says you can't do that. Its goal is

"common ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange,"

which, according to Karl Marx, is one of the steps toward economic

utopia. This utopia has never come about, and along the way, if you don't

allow private ownership, you end up with all businesses government-controlled.

This is bad for efficiency because businesses can only do what central

planners tell them to; you no longer have independent enterprises

trying out new ideas freely. And of course it is bad for

freedom because it prohibits private enterprise.

(2) A milder form of (1), sometimes called state capitalism, where

capitalism still operates, but the government is a major business owner.

This sometimes arises as a way to jump-start a developing country that doesn't

have enough investors; sometimes as a way to rescue corporations that are

in trouble but are considered necessary for the national good;

and sometimes as a way to run companies

where competition isn't practical, such as providing water to a city.

The trouble with state capitalism is that it gives the government a role

other than — well — governing. Will the government treat

businesses differently if it owns some of them? Will it favor the ones it

owns? How much freedom does private enterprise lose when state capitalism

comes in?

Another problem is that the government may be investing in businesses that

are not good enough for private investors, dooming itself to take a loss.

Should government impose losses like this on the taxpayers? And if the businesses

don't need to attract investors, do they even have an incentive to do their job right?

Again, there

are costs to be weighed.

I'm not saying state capitalism is never a good thing. But it does need to be

justified in every particular case. And some examples of it are whimsical.

For example, even the most politically conservative local leaders often favor

using government investment to build sports arenas.

(3) A separate thing often called socialism is simply

big government with lots of government services.

This is often favored by the same people as (1) or (2) but is actually

a separate matter; it has nothing to do with who can own businesses.

And it is not so much a system to be opposed

as a question of degree.

What services should be provided by government rather than private enterprise?

Nobody objects to having the government run the army or even the

fire department. Many of us favor some kind of government aid to the

truly needy; not only is it humane, it benefits the whole economy.

(And it makes aid available on the same terms to every needy person,

not just those with generous friends and neighbors.)

Government-provided health care is more controversial.

And so on...

I do not believe all the legitimate functions of government had been invented

by, say, 1785, or 1820, or whatever date you want to pick.

Genuinely new needs and opportunities arise.

But at every step we have to ask the difficult question,

is it better for this service to be provided by government

than by private enterprise?

It's not enough to show that we need the service; it's also necessary

to show that government is the best way to provide it,

and that in doing so, it is not either costing too much,

or needlessly eroding people's freedom.

(4) Yet another thing called socialism

is leveling of incomes and results.

This is seen by some as way to implement Karl Marx's dream (1), but it takes on

a life of its own as people come to believe that, very simply,

nobody should be allowed to become too rich.

This might arise from Marx's doctrine that business owners have no right to profit

from the workers; but it more often comes from the false belief that there

only a fixed amount of wealth in the world, so the only way people get richer is

by making others poorer.

Actually, of course, it is quite possible to get richer by making other people richer,

by causing productive work to be done. If an investor builds a factory and

gives the people of a village higher-paying jobs, is he stealing from

them? Is he getting rich by taking wealth away from them? Surely not. He is

enabling them to make a product that people will pay for, and as a result,

not only does he get more money than he had before, so do they. That is capitalism

in a nutshell.

Leveling is implemented by putting very high taxes on the rich, not just because money

has to come from somewhere and they can spare it, but because the goal is to stop

people from getting rich, so that no one will be wealthier than anyone else.

This kind of socialism tries to do foolish things to people's incentives and

opportunities. The naive underlying goal is that nobody should end up better off

than anybody else.

I have actually heard a socialist (of this kind)

say that rich people should have to send their

children to bad schools in order to take away their advantage.

The absurdity of leveling becomes clearer if you apply it to things

other than money. Do we want

our best musicians, actors, and pro athletes

not to be as good, in order to open up opportunities

for less talented people? Our best scientists and inventors?

Our best doctors?

Ultimately, as Sir James Mirrlees demonstrated at length, leveling tells your best

people to stop working. The people who are in a position to be most productive

will only work enough to get the maximum permitted income. Beyond that, they gain nothing

by working rather than slacking.

One famous example involves Astrid Lindgren, the author of Pippi Longstocking.

Her books sold so well that in 1976, her marginal tax rate reached 102%.

What could she do but stop writing?

Fortunately, rather than allow socialism to kill Pippi, Sweden changed its tax policies.

One last note about the cost of various things called socialism.

Counting the cost in freedom and affordability is straightforward:

how much does something limit our choices, and how much does it cost?

But when we get to incentive, there is a paradox:

the strongest incentive to work does not give the greatest productivity.

How's that? Well, the incentive to work is strongest when people are

desperately poor and have to work hard to keep from starving.

That is a way to guarantee that everybody works as much as they can.

But in that situation, they can't take time out to get an education,

maintain their health, or carry out business ventures that don't

pay instantly. Their productivity is low.

That's why modern governments give people such things as free

education, medical and financial aid for the poor, and regulations on

working conditions. The goal is high long-term national productivity, not

maximum pressure on every individual to work all the time.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2020

February

22

|

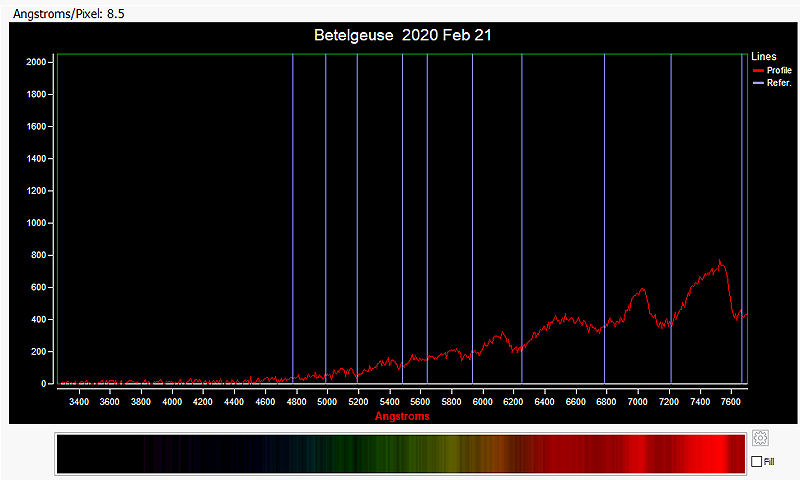

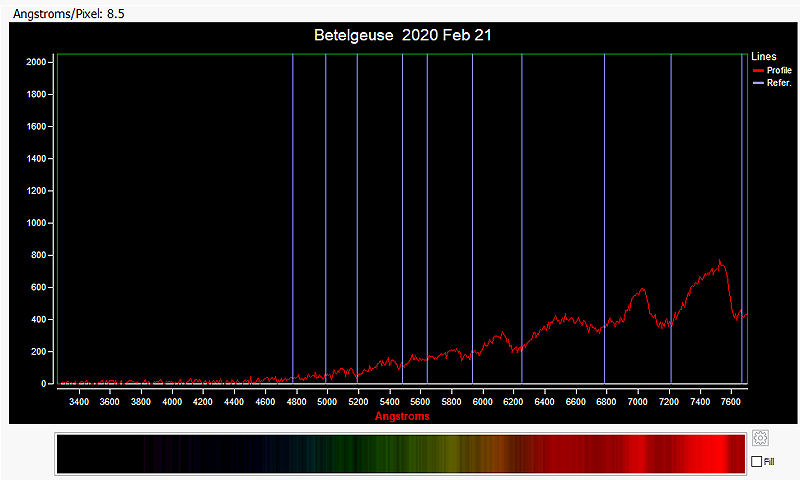

Spectrum of Betelgeuse

Here's the spectrum of Betelgeuse, captured with the same

equipment and software that I've used several times recently.

(Click here to find out how to get one.)

And what a spectrum it is! This is a star that

is mostly red, because it is not hot enough to glow yellow or white,

and is full of heavy elements (rather than hydrogen) because it has been fusing atoms for a long time.

Perhaps surprisingly, the big absorption bands in the spectrum are due to

titanium oxide (common in minerals on earth).

Blue lines mark their positions.

Also, I was surprised to learn that titanium oxide does not have an exact chemical formula.

The ratio of Ti to O varies.

On earth, TiO exists as impure crystals that are anywhere from about 40% to 60% titanium.

In a star, it is of course a gas of TiO molecules.

The titanium white paint pigment that we use on earth is TiO2.

Discussion at the AAVSO tells me the spectrum of Betelgeuse

has not actually changed much with

its recent variations in brightness.

Permanent link to this entry

Three galaxies

Last night I also took a couple of other astrophotos, mainly as a shakedown

for equipment I hadn't used in about three months (during our awful weather).

Here's the galaxy M81, with M82 above it and NGC 3077 to the left.

The noteworthy thing about M82 (the top one) is its active, turbulent central area.

AT65EDQ telescope (6.5-cm f/6.5), modified Nikon D5500, AVX mount, no guiding

corrections. Stack of ten 1-minute exposures.

Permanent link to this entry

Orion Nebula

I photograph the Orion Nebula every winter, so here it is for 2019-20. This is not a

very noteworthy picture; I've taken many other good pictures of the same object.

Same telescope and camera as above, stack of 6 1-minute exposures.

Some HDR processing was done on the midtone areas.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2020

February

21

|

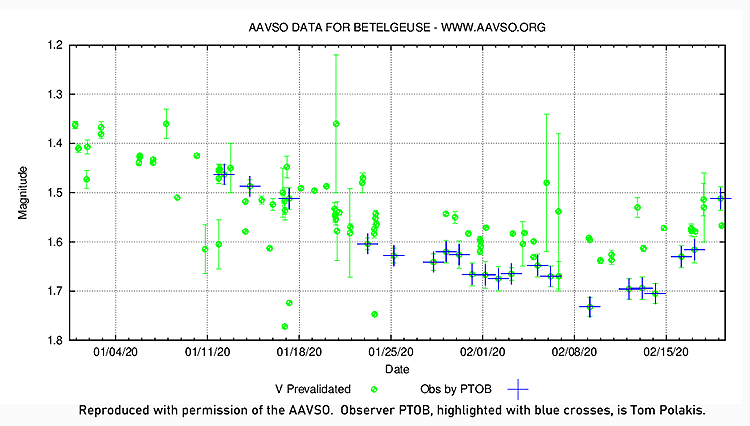

Betelgeuse is rebrightening

The star Betelgeuse in Orion has recently been much dimmer than its normal range

of variation. (It is a red giant star, and, like other red giants, pulsates over

a cycle of about 425 days, combined with a longer cycle

of about 6 years.) Now it's coming back.

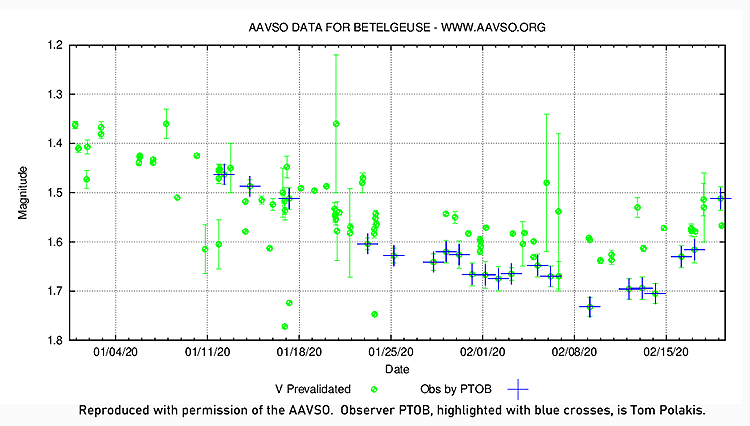

Here's some actual photometry. The observations marked with blue crosses are by

my friend Tom Polakis and are all with the same equipment, so they should be comparable.

This graph is reproduced with permission of the AAVSO (American Association of

Variable Star Observers). You can track Betelgeuse on their web site by

clicking here.

The rebrightening at this time

is consistent with the theory that Betelgeuse's two cycles of variation

simply happened to hit minimum at the same time, rather than anything

more ominous. Nonetheless, high-resolution imaging showed Betelgeuse as misshapen,

indicating, perhaps, a cloud of dust in front of it, or an enormous starspot

(quite plausible for that type of star). For a current scientific summary

see Wikipedia.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2020

February

20

|

Short notes

FormFree is keeping me busy. But here are a few notes about what has been going on

recently. I hope to catch up and write more before long.

All 5 grandchildren came for the visit, not just the 2 that you saw in the pictures.

I didn't mean to slight Mary, Philip, or Emily!

What Benjamin and I built was a battery box containing four AA cells.

This will power lots of educational experiments for the children.

During his visit, we did a short demonstration of a knife switch.

I'm thinking of writing a short book about electricity for children.

Gone are the days of the No. 6 Dry Cell and wires coiled into electromagnets —

we need LEDs, and maybe even diodes and transistors.

I can show a first-grader that a transistor is a device in which

electricity injected in one place

turns on a flow of electricity in another place.

And isn't that more than most people know about them?

We are having awful weather, including unusually heavy rain. That has kept

me from doing much astronomy. The brightness of Betelgeuse is probably

bottoming out right now, around magnitude 1.7, but all over America, fewer

than the usual number of people are getting to observe it.

We had an interesting conversation on Facebook about how to deal with

flat-earthers (who accost people like me giving astronomy presentations).

I contend that they do not really believe the earth is flat; they just want

to play a mind game or have a debating contest.

And my reply to them (which also works with cranks of other kinds) is,

"If you want to know the truth about the shape of the earth, seek it

honestly. It's not my job to persuade you of anything. The earth will

be round whether or not I beat you in a debating contest."

Permanent link to this entry

|

2020

February

5

|

What is this FormFree thing that I keep talking about?

I need to say a little more about how I’m spending my time

nowadays. Back during the economic

crisis of 2007-2009, I thought a lot about how mortgage lending in America had

gone wrong. Too many people were getting

loans who couldn’t pay them back, and the lenders should have known that.

I thought it was a problem, but since

mortgage lending is not my profession, all I could do was think about it and

occasionally express opinions.

I need to say a little more about how I’m spending my time

nowadays. Back during the economic

crisis of 2007-2009, I thought a lot about how mortgage lending in America had

gone wrong. Too many people were getting

loans who couldn’t pay them back, and the lenders should have known that.

I thought it was a problem, but since

mortgage lending is not my profession, all I could do was think about it and

occasionally express opinions.

Meanwhile, unknown to me, Brent Chandler was buying a house

and was daunted by how much time people had to spend reading computer printouts

and typing the numbers into another computer.

He started a business, FormFree,

to help lenders get the information they

needed directly from financial institutions.

From the start, FormFree’s goal

was to make loan underwriting smarter and wiser, not just faster.

People were starting to notice that loans

were being made on the wrong criteria, and FormFree

could fix that, by providing the information lenders actually needed.

So when Brent called

me up, I was glad to help him explore how AI could be put

to good use. I was delighted to be able

to actually do something about a major economic problem.

At the same time, I felt that I was moving outside my career

path. Most of my academic research was

in natural language processing and computational psycholinguistics (www.ai.uga.edu/caspr).

I’m not an economist, but creative use of

computers is right up my alley, and we were getting results, so I

persevered. After all, if everybody

stuck to just what they were trained in, original work would never get done.

In fact, as it turns out, some of FormFree’s

research is remarkably close to natural language processing.

When FormFree

analyzes a borrower’s financial situation, lots of details on bank statements

have to be recognized and interpreted.

This task is too complicated for traditional computer programming, nor

is machine learning much help at the start (though it comes in later).

What it’s like is natural-language

grammar. Details, details, details – but

I’m a linguist, and I’m accustomed to details. So in spite of the seeming impossibility,

we’re doing it.

Up to 2013 I was a University of Georgia faculty member,

doing consulting part-time with the University’s approval (it’s how the

University keeps its faculty in touch with industry).

When I retired, I ramped that up, although at

first not much, because of Melody’s and Sharon’s health problems.

I worked at home.

Well, FormFree has grown, and so

has my involvement with it, to the point that by now I’m well into a thriving

second career. At FormFree

I now have a job title (“Senior Research Scientist” – same as my UGA job title –

one might as well be consistent). I still

work at home or at variable locations (library, coffee shop, or

FormFree offices) on a flexible schedule, so that I can

still take care of Melody and Sharon.

My mother, a manager at the Credit Bureau of Athens, never

foresaw that I would be part of the credit industry, and she’d be tickled pink.

I should add that for tax reasons and to keep my skills

sharp, I am still also an independent consultant, though on a small scale.

So Covington Innovations is still in business. I continue to do R&D also for a

defense-related project whose details are not made public, and several other

smaller projects, though I am not actively soliciting more.

The Daily Notebook remains my personal blog, not

associated with FormFree in any way, which is why FormFree’s

name does not appear in the masthead at the top of each page.

Permanent link to this entry

|