|

How to twist wires together to make a soldered splice

Now for something completely different. People have stopped

sending me military secrets and messages of alarm, and I can get back

to doing what I enjoy — collecting useful knowledge and

then repackaging it for you.

In this case, a whole blog entry about how to twist wires together,

with over 100 years of history.

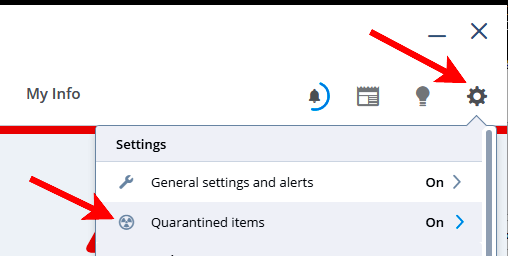

I've written about

soldering and about

crimp connectors several times. Today I want to address

something even simpler: how to twist wires together to splice them.

Most electronics books say very little about these important manual skills.

The splices I'm about to describe are intended to be soldered.

They do not have enough mechanical strength if the wires are just

twisted together and taped — the wires could be pulled out.

So don't skip the soldering step. If you're not going to solder, use some type

of approved solderless connector.

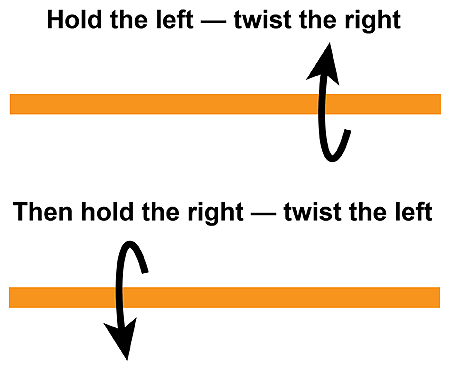

It's easy to twist wires together crudely, but I'm about to describe how to do it a bit

more neatly and reliably than you otherwise might. The two splices I'm going to describe

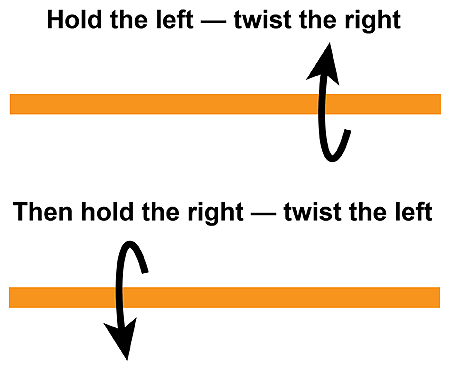

are both based on a pair of twisting motions, where you twist one way with your

right hand and then the other way with your left:

The two twists are the two ends of a single helix — the wire doesn't reverse

direction in the middle.

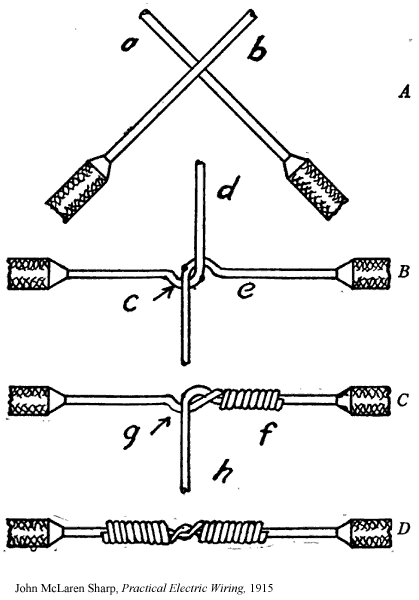

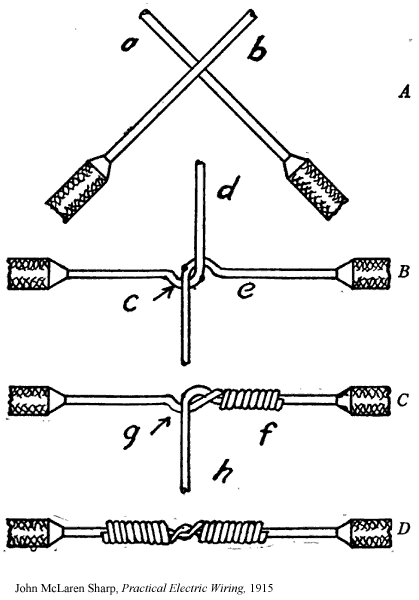

Both of these joints are descendants of the famous

Western Union lineman's splice, which can be immensely

strong when made with strong solid wire. That is where we got the idea of

using two opposite twisting motions.

The classic lineman's splice has a place in the middle where both wires run side

by side to make sure solder reaches both of them. When it's 1915 and you're soldering with a gasoline

torch and no flux, that can be an important precaution. But today, we have no trouble getting

our solder to soak into the entire joint, and we can make it a little more compact.

So...

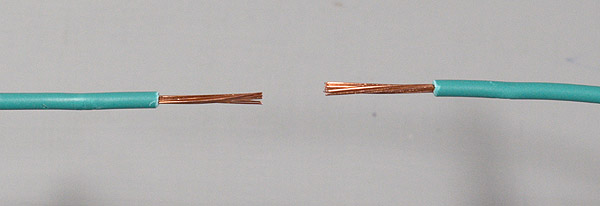

Modified lineman's splice

This is for solid or stranded wire.

(1) Strip insulation from both wires, about 1.5 to 2 times the total length of the finished splice.

Cross them about 1/3 or 1/4 of the way from the end of the insulation.

(Common mistakes are not to remove enough insulation, or to cross the wires too far out.)

(2) Wrap one end of the left wire compactly around the part of the right wire that is below the crossing.

(3) Complete the splice by doing the same on the other side.

Then solder, and you're done. This joint has only moderate mechanical strength before you

solder it; the wires can be pulled apart, but the splice is not fragile and not likely

to come apart accidentally, even with a good bit of movement.

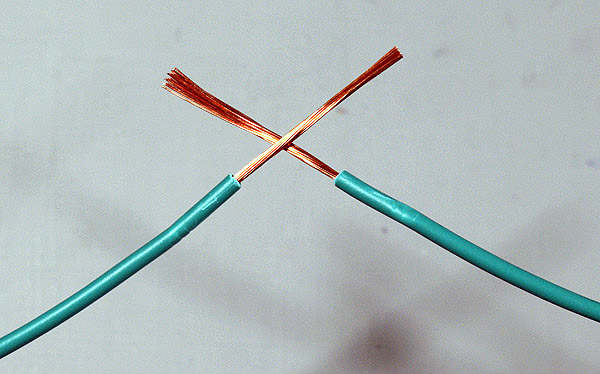

Mesh splice

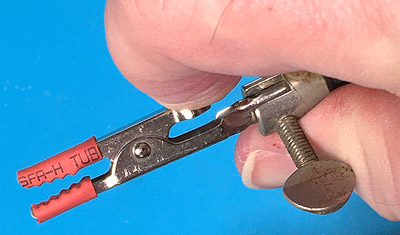

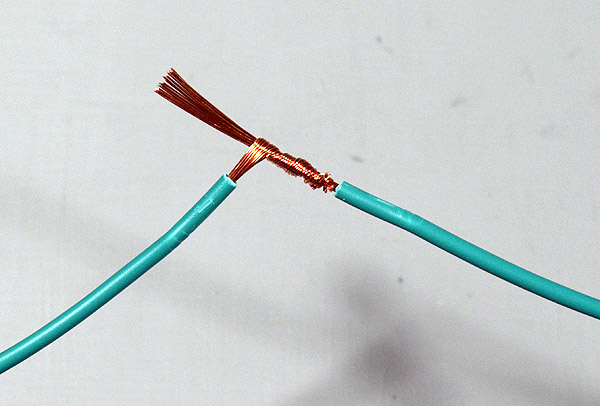

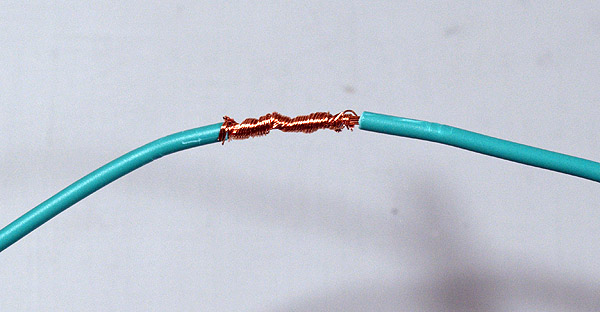

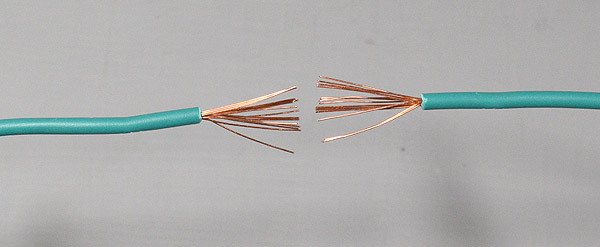

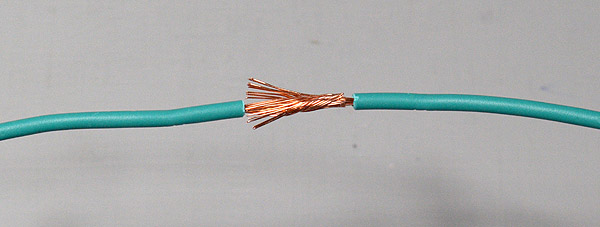

This is only for stranded wire, and it's easy to do wrong. Done right, it is a two-step process, and you can

see that it is descended from the classic lineman's splice, although it has little

mechanical strength until soldered.

(I've seen many people do this, but you may find

this video by "Wranglerstar"

particularly helpful.)

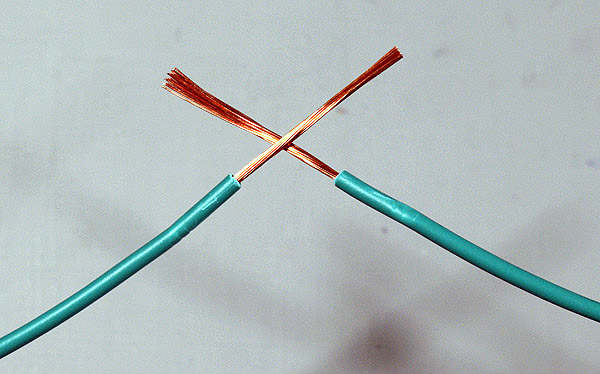

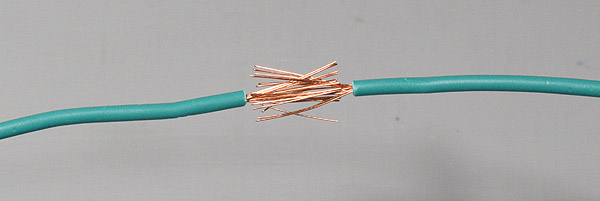

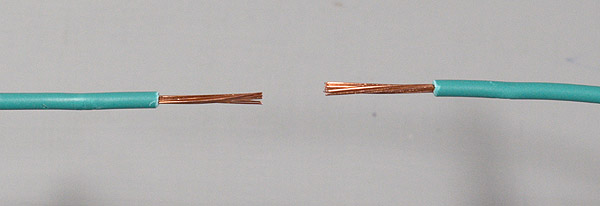

(1) Strip insulation from each wire for a length equal to the length of the

finished splice.

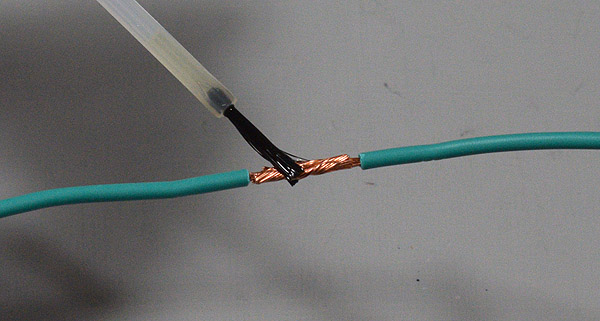

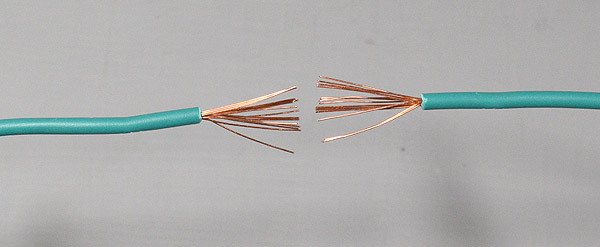

(2) Splay the strands apart, either individually or in bunches.

(3) Push the wires together so that the strands mesh.

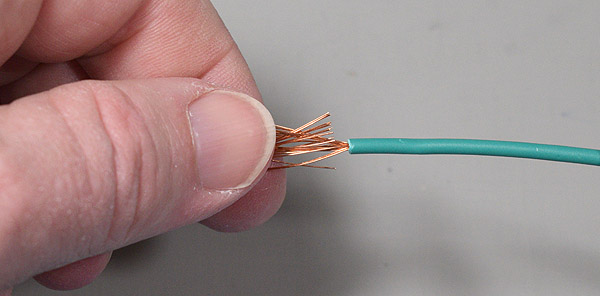

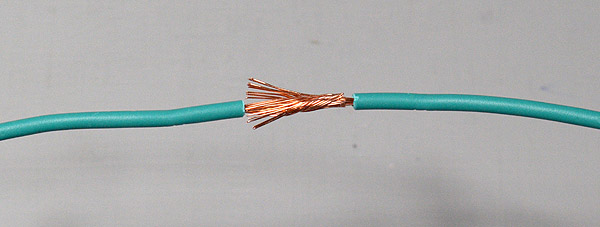

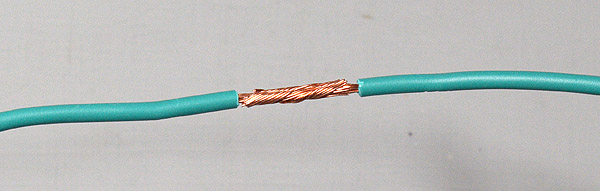

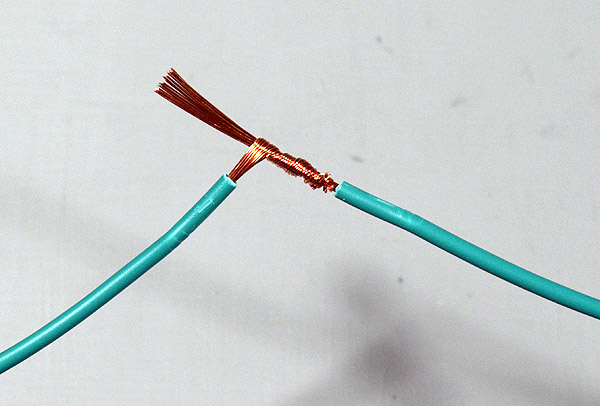

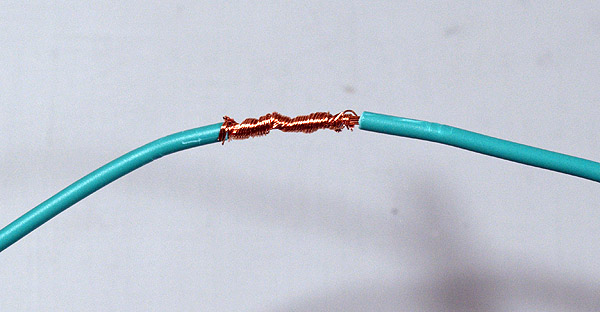

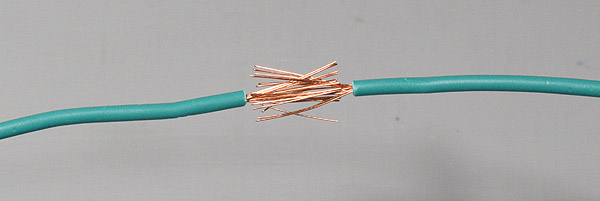

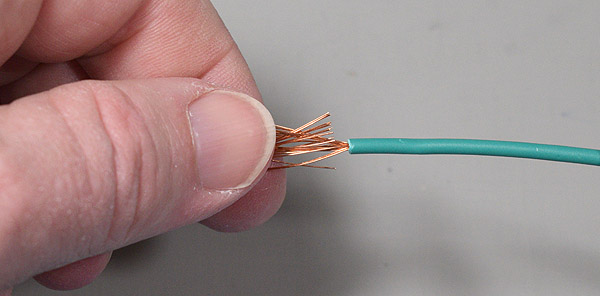

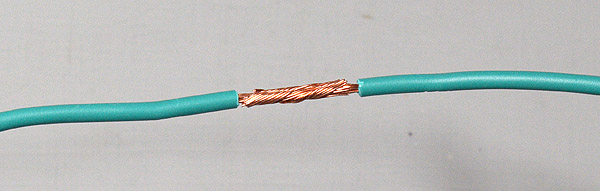

(4) Grip the left-hand end of the splice, and use your other hand to twist the right-hand end.

Here's what you'll end up with:

(5) Finish the splice by gripping on the right and twisting on the left.

Do not pull on the wires until they are soldered.

The mesh splice is very easily pulled apart.

And then what?

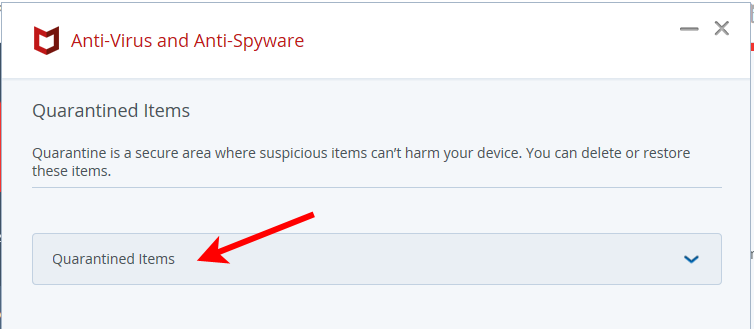

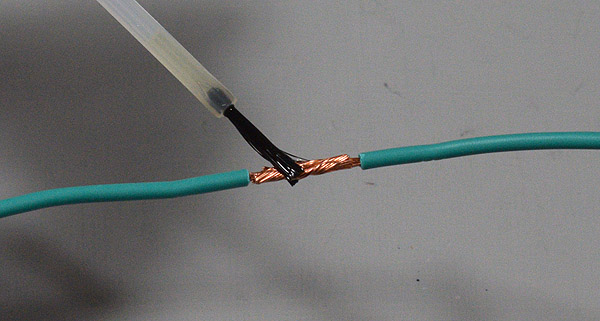

By popular demand I'm adding the following pictures to show you what happens

to a splice after the wires are twisted. First I add flux (to remove corrosion

so the solder will adhere better):

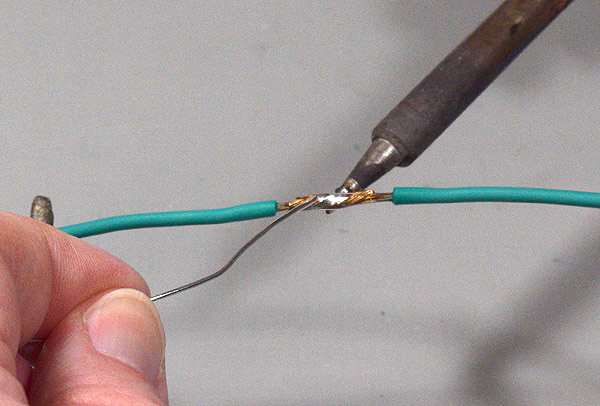

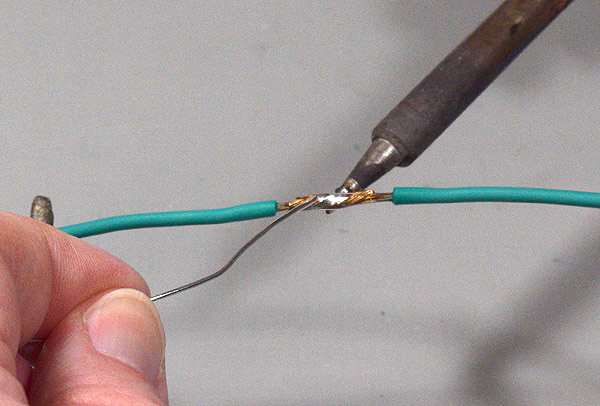

Then I apply solder. The tip of the soldering iron needs to be clean and have

melted solder on it for heat conduction; a surprising amount of this melted solder

is taken up by the copper wires immediately, and more has to be added.

But the solder that will make the joint is applied from the top while

heat is applied from the bottom:

Here is what the splice looks like with most of the solder on; as seen here,

it still needs a little more:

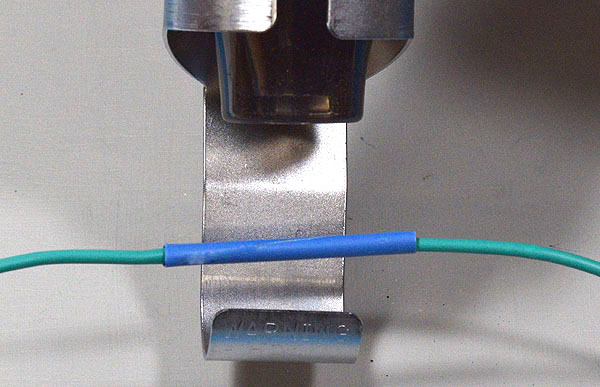

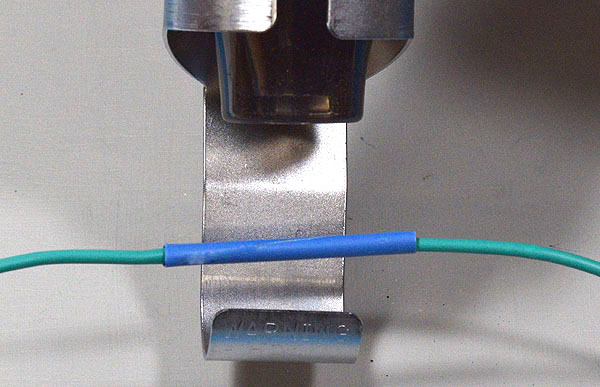

Next step is to slip a piece of heat-shrink tubing over the splice.

(Trap for the unwary: If the other end of at least one of the wires isn't open, you need to hop

into your time machine, go back to before you made the splice, and slip

the heat-shrink tubing on, leaving it farther down the wire until it's needed.)

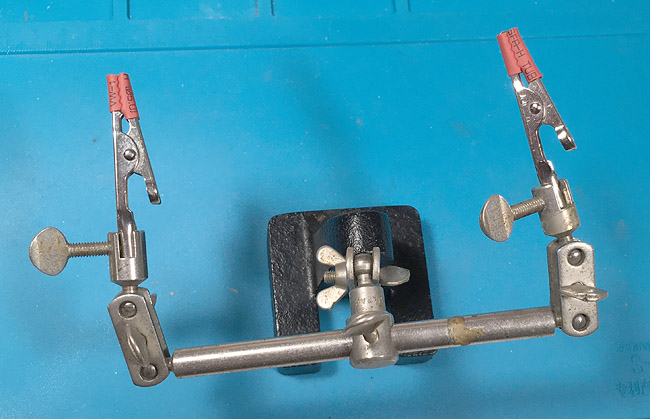

Next step is to make the tubing shrink. I use a special, small heat gun that I got

at Radio Shack (back when there was still such a thing); other hot-air guns

and even lighters will work.

And now you know the whole process. When great durability is needed, I

sometimes add a second layer of heat-shrink tubing.

Why did I do this? Not just to tell someone (who?) how to splice wires,

but also to get experience illustrating things like this. The camera was my

Nikon D5300, not entirely satisfactory because its self-timer is good for only

5 seconds and has to be set by pressing two buttons (besides the shutter button)

before taking each picture. Five seconds is not a lot of time to go from pushing

a button on the camera to holding the soldering iron and solder.

I think I'll use the old Canon 40D for pictures like this in the future;

fewer megapixels, but more professional features.

But I did have an interesting time using Adobe Illustrator to make the diagram

at the beginning, about twisting in two directions.

Permanent link to this entry

|